SUDAN, AN ENDLESS WAR

The Dinka people

of southern Sudan are not concerned with the details of time and number,

measuring their lives instead by the passage of the wet and the dry seasons.

So Ayk Maker isn't sure how many times she and her family have been attacked

and chased from their home, remembering only that it has happened again

and again. The Dinka people

of southern Sudan are not concerned with the details of time and number,

measuring their lives instead by the passage of the wet and the dry seasons.

So Ayk Maker isn't sure how many times she and her family have been attacked

and chased from their home, remembering only that it has happened again

and again.

At first she and her husband lived in relative peace and prosperity,

tending a few head of cattle and scraping together a living out of their

three mud huts in Bahr El Ghazal province, one of the least developed regions

in the world. Occasionally Arab looters would swoop into the village on

horses to steal food and cattle, but that was normal and the Dinka accepted

it as their lot.

But in recent years the civil war that has been raging in southern Sudan

for 15 years touched the people here directly. A local warlord, Karubino

Bol, sided with the forces of the northern Islamic government two years

ago, launching a massive campaign of terror.

"We were attacked and our property was taken away by the people

of Karubino," Ayk Maker says. "When Karubino came the attacks

became very common. I don't know how many there were. All I know is that

for years now we have been running."

Whenever the people heard gunshots ringing out across the vast, barren

plains, they would run for two days to a safer area across the river. One

time Ayk Maker's son, Dol, was born while the family was escaping. "It

was very difficult (to give birth on the run) but when you are running

for your life everything becomes easy," she says.

For two years, the family survived on the move, making temporary shelters

and eating mainly food they could gather from the land. Then in January

this year, Karubino defected yet again, this time back to the rebel Sudan

People's Liberation Army, and peace returned to Bahr El Ghazal.

An estimated 100,000 people, including Ayk Maker and her two children,

returned to their houses, only to find them burnt and looted, their cattle

gone and their ability to cultivate the land destroyed. "We have to

accept it," says Ayk Maker. "It has happened and we just have

to rebuild."

The resilience of the Dinka people is truly remarkable. Time and again

they have started from scratch, rebuilding their houses and planting their

fields, only to lose everything to natural disasters and the civil war.

Even in these most cruel of circumstances, their humor and dignity has

not deserted them.

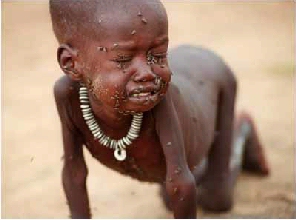

But the years of displacement have had a cumulative effect, and, after

two years of poor harvests, conditions now are worse than ever. Emaciated

children crowd the feeding centre next to Ayk Maker's house, their bellies

distended with worms and the failure of their abdominal muscles, the fat

reserves in their cheeks eaten away so young babies have the appearance

of old men.

Things can only get worse unless the people plant in the next few weeks

for a September harvest, and, even so, the threat of starvation for up

to half a million people is a real possibility. Again, the tragedy of southern

Sudan is demanding international intervention to avert a catastrophe.

Because of the war, more than a million civilians have died and several

million have been displaced internally or sent fleeing into neighboring

countries, their homes destroyed and their ability to feed themselves diminished.

There have been widespread human rights abuses on both sides of the conflict,

slavery has flourished, forced Islamisation of the population is continuing

and civilians have been directly targeted by the warring factions.

Fighting began after independence from the British in 1956, and, after

a lull between 1972 and 1983, has been raging unabated for 15 years. It

pits the Islamic Arab regime in the north against the Christian and animist

black southerners, who are fighting against the imposition of the fundamentalist

Islamic shari'a law and for self-determination in the south.

Sudan is considered a pariah state by the West due to its export of

Islamic terrorism and attempts to destabilise neighboring countries such

as Uganda, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Egypt. Fearing the civil war may develop

into a more bloody regional conflict, many of the black African countries,

as well as the West, have thrown their support behind the rebel army.

Of course, there is more to the war than ideology. The south, while

under-developed now, is highly fertile and has huge potential for food

and timber production.

There are also untouched gold and oil deposits there, while both sides

of the conflict have benefited from arms trading, profiteering and smuggling.

In the past two months the rebel army has made considerable gains, leaving

government troops stranded in a few isolated strongholds. Peace talks are

scheduled to take place on 4 May, and the international community has called

this week for a ceasefire to be declared so aid can get through.

But analysts say neither side has much to gain from calling an end to

the war. "It's doubtful the peace talks are going to achieve much.

Not because they cannot, but because neither group wants them to achieve

much," says Ms Josephine Odera, a Sudan analyst.

She says the Government is unlikely to call an end to hostilities because

it is negotiating from a weakened position, while the army has nothing

to lose by continuing its offensive.

Years of oppression by the northern regime have left the Dinka disenfranchised

from the start - the south has literally no education, health or infrastructure,

and the Government has deliberately kept it that way.

The most recent fighting has now taken away the people's very means

of survival. They are no longer able to trade and exchange, they have lost

the incentive to cultivate crops because the threat of dislocation is so

high, and they have lost their cattle - normally the source of up to 60

per cent of their food income through trade as well as milk production.

"People are denied basic rights by the Government of Sudan in the

areas the SPLA controls," says Bruce Menser, the Sudan/Somalia relief

program director at World Vision.

"The Government doesn't care about the people of southern Sudan.

They care about the land, the oil, they care about power and control, but

they don't care about the people."

The civil war has not only created the disaster that is now facing the

people of Bahr El Ghazal, but it is also hindering efforts to help them.

World Vision says in a 1996 policy paper on Sudan: "Access to any

sort of humanitarian aid is increasingly at risk due to the intransigence

of the Government of Sudan."

Aid to southern Sudan is controlled by Operation Lifeline Sudan, a tripartite

agreement between the Government, the UN and other aid agencies, and the

army. This means the Government is able to veto aid in the south by withdrawing

clearance for flights. The Government, fearing aid will benefit the rebels,

imposed a total flight ban for two months earlier this year, which prevented

thousands of tonnes of food being delivered and caused the situation to

deteriorate to its present level.

Even worse, the Government has been systematically targeting the civilian

population in the south, accusing the people there of backing the opposition.

Bombings of hospitals and feeding centres are regular and have cost hundreds

of lives.

Aid agencies are having to tread carefully. They are operating in a

rebel-held area where there is effectively no government, and security

is a major concern.

They are also battling a severe lack of funding. The World Food Program

has a shortfall of

$US37 million out of a total of $49 million for southern Sudan, while

Unicef needs another $2 million to fly in seeds and tools. All aid agencies

operation in the region say the public response to their appeals has been

slow.

"I think there are growing needs all the time in this region and

donors just cannot keep pace with it - they have to respond to the most

urgent cases. The question is whether they can respond in time," says

Brenda Barton, a spokeswoman for the World Food Program.

The workers in Bahr El Ghazal are seeing hundreds of starving children

every day, repeatedly hearing stories of displacement and tragedy.

Last week, says Bjorn Rugsten, a young World Vision worker at the Panacier

feeding centre, a woman came right to the gate of the compound, squatted

down and gave birth.

By the time the baby was born, she had missed the food distribution

for that day, but she was so hungry she picked up the infant and ran to

try to salvage what grain she could.

The woman and her baby are now being fed by World Vision. But for the

aid workers at Panacier, the incident has epitomised the level of human

degradation and suffering that the hunger has brought.

"That really shook me up," Mr Rugsten says. "I was in

Somalia in '92-93 and that was

really bad, but the situation here is really pathetic.

"People say you shouldn't use the word `famine' because it's too

strong, but maybe I can put it like this - the people don't have any tools

or seeds to start up their life. It's not enough that they are hungry,

but they don't have anything to start up with.

"They are giving you all this trust that you will help but you

can't help everyone. You are playing God here."

|